Convergence problem

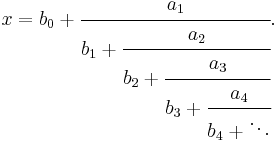

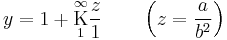

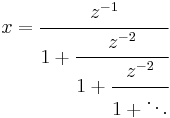

In the analytic theory of continued fractions, the convergence problem is the determination of conditions on the partial numerators ai and partial denominators bi that are sufficient to guarantee the convergence of the continued fraction

This convergence problem for continued fractions is inherently more difficult (and also more interesting) than the corresponding convergence problem for infinite series.

Contents |

Elementary results

When the elements of an infinite continued fraction consist entirely of positive real numbers, the determinant formula can easily be applied to demonstrate when the continued fraction converges. Since the denominators Bn cannot be zero in this simple case, the problem boils down to showing that the product of successive denominators BnBn+1 grows more quickly than the product of the partial numerators a1a2a3...an+1. The convergence problem is much more difficult when the elements of the continued fraction are complex numbers.

Periodic continued fractions

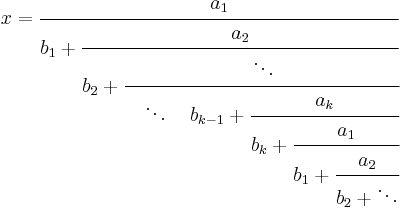

An infinite periodic continued fraction is a continued fraction of the form

where k ≥ 1, the sequence of partial numerators {a1, a2, a3, ..., ak} contains no values equal to zero, and the partial numerators {a1, a2, a3, ..., ak} and partial denominators {b1, b2, b3, ..., bk} repeat over and over again, ad infinitum.

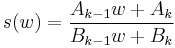

By applying the theory of linear fractional transformations to

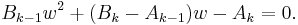

where Ak-1, Bk-1, Ak, and Bk are the numerators and denominators of the k-1st and kth convergents of the infinite periodic continued fraction x, it can be shown that x converges to one of the fixed points of s(w) if it converges at all. Specifically, let r1 and r2 be the roots of the quadratic equation

These roots are the fixed points of s(w). If r1 and r2 are finite then the infinite periodic continued fraction x converges if and only if

- the two roots are equal; or

- the k-1st convergent is closer to r1 than it is to r2, and none of the first k convergents equal r2.

If the denominator Bk-1 is equal to zero then an infinite number of the denominators Bnk-1 also vanish, and the continued fraction does not converge to a finite value. And when the two roots r1 and r2 are equidistant from the k-1st convergent – or when r1 is closer to the k-1st convergent than r2 is, but one of the first k convergents equals r2 – the continued fraction x diverges by oscillation.[1][2][3]

The special case when period k = 1

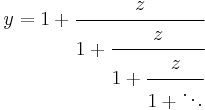

If the period of a continued fraction is 1; that is, if

where b ≠ 0, we can obtain a very strong result. First, by applying an equivalence transformation we see that x converges if and only if

converges. Then, by applying the more general result obtained above it can be shown that

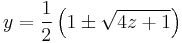

converges for every complex number z except when z is a negative real number and z < −¼. Moreover, this continued fraction y converges to the particular value of

that has the larger absolute value (except when z is real and z < −¼, in which case the two fixed points of the LFT generating y have equal moduli and y diverges by oscillation).

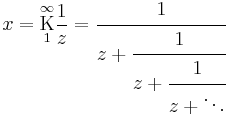

By applying another equivalence transformation the condition that guarantees convergence of

can also be determined. Since a simple equivalence transformation shows that

whenever z ≠ 0, the preceding result for the continued fraction y can be restated for x. The infinite periodic continued fraction

converges if and only if z2 is not a real number lying in the interval −4 < z2 ≤ 0 – or, equivalently, x converges if and only if z ≠ 0 and z is not a pure imaginary number lying in the interval −2i < z < 2i.

Worpitzky's theorem

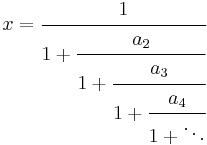

By applying the fundamental inequalities to the continued fraction

it can be shown that the following statements hold if |ai| ≤ ¼ for the partial numerators ai, i = 2, 3, 4, ...

- The continued fraction x converges to a finite value, and converges uniformly if the partial numerators ai are complex variables.[4]

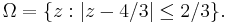

- The value of x and of each of its convergents xi lies in the circular domain of radius 2/3 centered on the point z = 4/3; that is, in the region defined by

- The radius ¼ is the largest radius over which x can be shown to converge without exception, and the region Ω is the smallest image space that contains all possible values of the continued fraction x.[5]

The proof of the first statement, by Julius Worpitzky in 1865, is apparently the oldest published proof that a continued fraction with complex elements actually converges.[6]

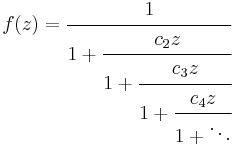

Because the proof of Worpitzky's theorem employs Euler's continued fraction formula to construct an infinite series that is equivalent to the continued fraction x, and the series so constructed is absolutely convergent, the Weierstrass M-test can be applied to a modified version of x. If

and a positive real number M exists such that |ci| ≤ M (i = 2, 3, 4, ...), then the sequence of convergents {fi(z)} converges uniformly when

and f(z) is analytic on that open disk.

Śleszyński–Pringsheim criterion

In the late 19-th century, Śleszyński and later Pringsheim showed that a continued fraction, in which the as and bs may be complex numbers, will converge to a finite value if  for

for  [7]

[7]

Van Vleck's theorem

Jones and Thron attribute the following result to Van Vleck. Suppose that all the ai are equal to 1, and all the bi have arguments with:

with epsilon being any positive number less than  . In other words, all the bi are inside a wedge which has its vertex at the origin, has an opening angle of

. In other words, all the bi are inside a wedge which has its vertex at the origin, has an opening angle of  , and is symmetric around the positive real axis. Then fi, the ith convergent to the continued fraction, is finite and has an argument:

, and is symmetric around the positive real axis. Then fi, the ith convergent to the continued fraction, is finite and has an argument:

Also, the sequence of even convergents will converge, as will the sequence of odd convergents. The continued fraction itself will converge if and only if the sum of all the |bi| diverges.[8]

Notes

- ^ 1886 Otto Stolz, Verlesungen über allgemeine Arithmetik, pp. 299-304

- ^ 1900 Alfred Pringsheim, Sb. München, vol. 30, "Über die Konvergenz unendlicher Kettenbrüche"

- ^ 1905 Oskar Perron, Sb. München, vol. 35, "Über die Konvergenz periodischer Kettenbrüche"

- ^ 1865 Julius Worpitzky, Jahresbericht Friedrichs-Gymnasium und Realschule, "Untersuchungen über die Entwickelung der monodromen und monogenen Functionen durch Kettenbrüche"

- ^ a b 1942 J. F. Paydon and H. S. Wall, Duke Math. Journal, vol. 9, "The continued fraction as a sequence of linear transformations"

- ^ 1905 Edward Burr Van Vleck, The Boston Colloquium, "Selected topics in the theory of divergent series and of continued fractions"

- ^ See for example Theorem 4.35 on page 92 of Jones and Thron (1980).

- ^ See theorem 4.29, on page 88, of Jones and Thron (1980).

References

- Jones, William B.; Thron, W. J. (1980), Continued Fractions: Analytic Theory and Applications. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications., 11, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, ISBN 0-201-13510-8

- Oskar Perron, Die Lehre von den Kettenbrüchen, Chelsea Publishing Company, New York, NY 1950.

- H. S. Wall, Analytic Theory of Continued Fractions, D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1948 ISBN 0-8284-0207-8